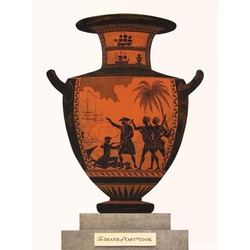

THE ODYSSEY OF CAPTAIN COOKFirst exhibited in 2005

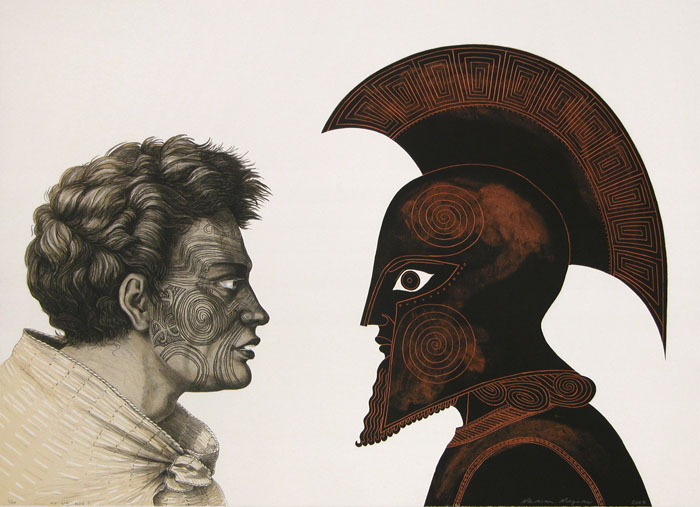

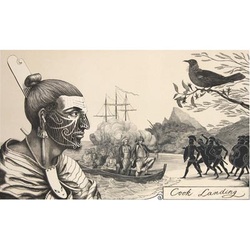

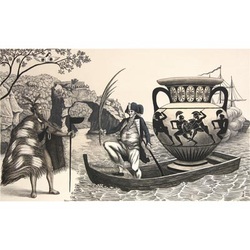

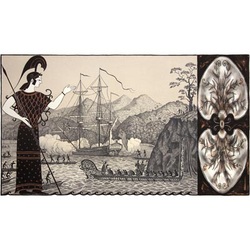

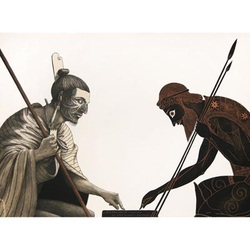

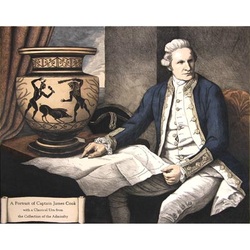

10 lithographs An imagined meeting between ancient Greeks and the Maori of New Zealand brought about by the arrival of the Endeavour in the late eighteenth century. Excerpts from Anna Smith's essay 'Ode on a South Seas Urn' from the catalogue of 'The Odyssey of Captain Cook' (2005): 'What do the Ancient Greeks have in common with the South Seas? A lot, if a certain master printmaker from Christchurch has anything to do with it. Artist Marian Maguire has been working on bringing the Greeks to New Zealand for a number of years now. Inspired by the designs of classical artefacts: urns, bowls and jugs, Maguire has reworked the meeting of English colonisers and Maori through the medium of classical shapes and figures. In this new show, the collision of three cultures, not two, takes the viewer by surprise. The Odyssey of Captain Cook takes radical liberties with the history of this country, for we discover that Pakeha and Maori have now been joined by chiefs from the heavens (Arikirangi): Achilles, Athena, and boatloads of Greek soldiers. Using the voyages of Captain Cook as the pretext, Maguire explores how a nation remembers and represents its history. By implication, she also explores what a nation leaves out when it remembers; and how its vision is always skewed in favour of one race or the other. Every time we seek to understand these engravings and lithographs as the story of two nations, or two races, the artist presents a third perspective: a sleight of hand which, in a climate that favours biculturalism, makes for troubled viewing indeed. ... This is the work of a smart artist who finds that her head as well as her hands are good to think with. For there is definitely something unthinkable, undesirable even, in juxtaposing three alien worlds, when in post-colonial New Zealand we have been so accustomed to living with the collision of two. The closest one could come to putting the complex and fluid gestures embodied in this exhibition into words, is by suggesting that its ever-changing, three sided quality marks the artist’s commitment to staging a completely new myth.' "When we had left the island astern and no other land, or anything but sky and water, was to be seen, Zeus brought a sombre cloud to rest above the hollow ship so that the sea was darkened by its shadow." (The Odyssey, Book 12,401-402) |

Marian Maguire's introduction to 'The Odyssey of Captain Cook' catalogue (2005):

'Raised Catholic I was by an early age familiar with persuasive narrative images that cemented an accepted idea into the foundation of my world. Whether they were true or not was undisputed; that they made sense was what mattered.

While studying art at the University of Canterbury I completed part of my degree in Religious Studies. Although I tended toward the Eastern religions I completed a paper in Maori culture which, as I have remembered it, was about how a world-view incorporating the supernatural made greater sense of the apparent reality.

During my final year at Art School, and into the year following, I made numerous drawings from ancestral figures of Aotearoa and the Pacific. I spent hours sitting in Canterbury, Dunedin and Auckland museums concentrating on these ancient objects, now artefacts, which once had a life full of meaning and purpose outside institutional walls.

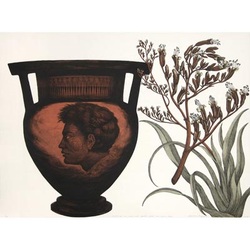

My early exhibited work was figurative and emblematic, much like the carvings. This later gave way to quite symbolic woodcuts and etchings of gates, archways and bridges. These led to an interest in architecture, mainly Catholic cathedrals, which landed me in Renaissance Italy, which inevitably brought me to Classical Greece, which sparked an interest in the storytelling on Greek vases, which links absolutely with my early interest in myth, narrative and meaning.

Why Captain James Cook? Because he brings me to my own location in the south of the Pacific, living the life of a Westerner amidst Polynesia. There is something about the Age of Discovery that fascinates me. It has to do with knowing that one is ignorant and searching for knowledge while carrying baggage even without realising it. I suppose the Greeks are baggage; stowaways on the ships of history, underpinning culture just as the Catholic Church of my early years did. Parallels and differences between ancient Greece, classical Maori and Captain Cook could be investigated ad infinitum but what I keep coming to, no matter which way I look at it, is that it's all about being human. I am in no way expert on the Greeks, late-eighteenth-century Britain or Maori culture present or past, and although I have great interest in each my understanding is limited by my own experience and background. However, I do connect with human emotions that come through the artistic expression of all three.

Trained as an artisan printmaker I have printed the lithographs of New Zealand artists for twenty years and have woven my own art making around and through this profession. I have a deep and intimate love of the printed artwork and also connect with the print-workers of previous eras, in particular the engravers of two to three hundred years ago. They translated, into reproduceable form, the drawings, watercolours and paintings of artists and draughtsmen of their day. Carving a network of fine lines into copper the engravers would painstakingly interpret drawings with unbelievable skill, at a time when there was no photography, no electric lighting, and a good pair of spectacles would have been a luxury.

ICaptain Cook took artists with him on each of the Pacific voyages and it is their visual investigation combined with written accounts that allowed Europe to gain insight into the Antipodes for the first time. Interest in fresh discoveries was keen but the number of drawings from exploratory missions was limited and copyright law was not yet established. Publishers therefore employed artisan engravers to copy other engravers' work in order to meet demand. As a result the same New World characters were fitted into various scenes as was convenient. Detail was guessed at, or fudged, and in this process of visual Chinese Whispers illustrations evolved that would be easily digested by an audience but were only approximately faithful to the original.

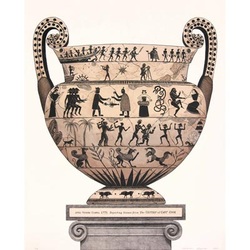

I am sure that a similar evolution would have occurred with The Odyssey. Whether fact or fiction the story became established in an oral tradition and by the time it was painted on vases or written down in Homeric verse the storyline had settled into myth; a myth that made sense in the society that created it. Like the engravers the vase painters worked with great dexterity. They expressed complex storylines and emotions on a curved surface within a tight visual language. Similar parameters existed for Maori carvers as they fashioned ancestors and mythic beings out of timber. Like the Greek vase painters their virtuosity was constrained by convention and expectation, for their carvings partnered an oral storytelling tradition and were made to fit a philosophically balanced societal whole.

While the hydrias, amphoras and craters of the classical world once served the banal function of wine or water carriers they have accidentally emerged with a second life in a manner their creators could not have predicted. At one time containers of the everyday they now carry the memory of a culture that, while no longer beating its rhythm, is part of the Western historical line. Empty but full vessels. In this way I have come to think of the Cook's Endeavour as a vessel, both full and hollow. Dwarfed by the huge expanse of the unmapped Southern Seas and loaded with the potential for adventure or tragedy the Endeavour headed into an unknown future, our past. It is testament to James Cook and his crew that they survived the First Voyage at all. To have completed the next two was a near miracle, even if on the last the ship was sailed home without its captain.

Ocean-going Polynesian craft also travelled at great risk through the vast Pacific and had in common with the Britain of the late eighteenth century a robust voyaging tradition. Intelligence and endurance were everything in a situation where tiny human lives bobbed on seemingly infinite salt water, exposed to the natural forces of unexplored realms. Homer, through the words of Odysseus, sums up the feeling of isolation, vulnerability and impending disaster that voyagers in these circumstances must have had to overcome.'

'Raised Catholic I was by an early age familiar with persuasive narrative images that cemented an accepted idea into the foundation of my world. Whether they were true or not was undisputed; that they made sense was what mattered.

While studying art at the University of Canterbury I completed part of my degree in Religious Studies. Although I tended toward the Eastern religions I completed a paper in Maori culture which, as I have remembered it, was about how a world-view incorporating the supernatural made greater sense of the apparent reality.

During my final year at Art School, and into the year following, I made numerous drawings from ancestral figures of Aotearoa and the Pacific. I spent hours sitting in Canterbury, Dunedin and Auckland museums concentrating on these ancient objects, now artefacts, which once had a life full of meaning and purpose outside institutional walls.

My early exhibited work was figurative and emblematic, much like the carvings. This later gave way to quite symbolic woodcuts and etchings of gates, archways and bridges. These led to an interest in architecture, mainly Catholic cathedrals, which landed me in Renaissance Italy, which inevitably brought me to Classical Greece, which sparked an interest in the storytelling on Greek vases, which links absolutely with my early interest in myth, narrative and meaning.

Why Captain James Cook? Because he brings me to my own location in the south of the Pacific, living the life of a Westerner amidst Polynesia. There is something about the Age of Discovery that fascinates me. It has to do with knowing that one is ignorant and searching for knowledge while carrying baggage even without realising it. I suppose the Greeks are baggage; stowaways on the ships of history, underpinning culture just as the Catholic Church of my early years did. Parallels and differences between ancient Greece, classical Maori and Captain Cook could be investigated ad infinitum but what I keep coming to, no matter which way I look at it, is that it's all about being human. I am in no way expert on the Greeks, late-eighteenth-century Britain or Maori culture present or past, and although I have great interest in each my understanding is limited by my own experience and background. However, I do connect with human emotions that come through the artistic expression of all three.

Trained as an artisan printmaker I have printed the lithographs of New Zealand artists for twenty years and have woven my own art making around and through this profession. I have a deep and intimate love of the printed artwork and also connect with the print-workers of previous eras, in particular the engravers of two to three hundred years ago. They translated, into reproduceable form, the drawings, watercolours and paintings of artists and draughtsmen of their day. Carving a network of fine lines into copper the engravers would painstakingly interpret drawings with unbelievable skill, at a time when there was no photography, no electric lighting, and a good pair of spectacles would have been a luxury.

ICaptain Cook took artists with him on each of the Pacific voyages and it is their visual investigation combined with written accounts that allowed Europe to gain insight into the Antipodes for the first time. Interest in fresh discoveries was keen but the number of drawings from exploratory missions was limited and copyright law was not yet established. Publishers therefore employed artisan engravers to copy other engravers' work in order to meet demand. As a result the same New World characters were fitted into various scenes as was convenient. Detail was guessed at, or fudged, and in this process of visual Chinese Whispers illustrations evolved that would be easily digested by an audience but were only approximately faithful to the original.

I am sure that a similar evolution would have occurred with The Odyssey. Whether fact or fiction the story became established in an oral tradition and by the time it was painted on vases or written down in Homeric verse the storyline had settled into myth; a myth that made sense in the society that created it. Like the engravers the vase painters worked with great dexterity. They expressed complex storylines and emotions on a curved surface within a tight visual language. Similar parameters existed for Maori carvers as they fashioned ancestors and mythic beings out of timber. Like the Greek vase painters their virtuosity was constrained by convention and expectation, for their carvings partnered an oral storytelling tradition and were made to fit a philosophically balanced societal whole.

While the hydrias, amphoras and craters of the classical world once served the banal function of wine or water carriers they have accidentally emerged with a second life in a manner their creators could not have predicted. At one time containers of the everyday they now carry the memory of a culture that, while no longer beating its rhythm, is part of the Western historical line. Empty but full vessels. In this way I have come to think of the Cook's Endeavour as a vessel, both full and hollow. Dwarfed by the huge expanse of the unmapped Southern Seas and loaded with the potential for adventure or tragedy the Endeavour headed into an unknown future, our past. It is testament to James Cook and his crew that they survived the First Voyage at all. To have completed the next two was a near miracle, even if on the last the ship was sailed home without its captain.

Ocean-going Polynesian craft also travelled at great risk through the vast Pacific and had in common with the Britain of the late eighteenth century a robust voyaging tradition. Intelligence and endurance were everything in a situation where tiny human lives bobbed on seemingly infinite salt water, exposed to the natural forces of unexplored realms. Homer, through the words of Odysseus, sums up the feeling of isolation, vulnerability and impending disaster that voyagers in these circumstances must have had to overcome.'